An area in the Gulf of Mexico has a high chance of becoming Tropical Storm Nestor.

At a Glance

- A broad area of low pressure is currently over the southwestern Gulf of Mexico.

- This so-called Central American gyre may spawn a tropical or subtropical storm in the Gulf of Mexico.

- This possible Gulf system is forecast to move toward the northern Gulf Coast this weekend.

- Heavy rainfall is possible in parts of the Southeast plagued by a recent flash drought.

- This system may also produce some surge flooding along and to the east of its track.

- Central American gyres have spawned notable Gulf tropical cyclones in recent years.

A tropical or subtropical storm is likely to form in the Gulf of Mexico over the next day or so and bring soaking rain, winds and coastal flooding to parts of the Southeast this weekend.

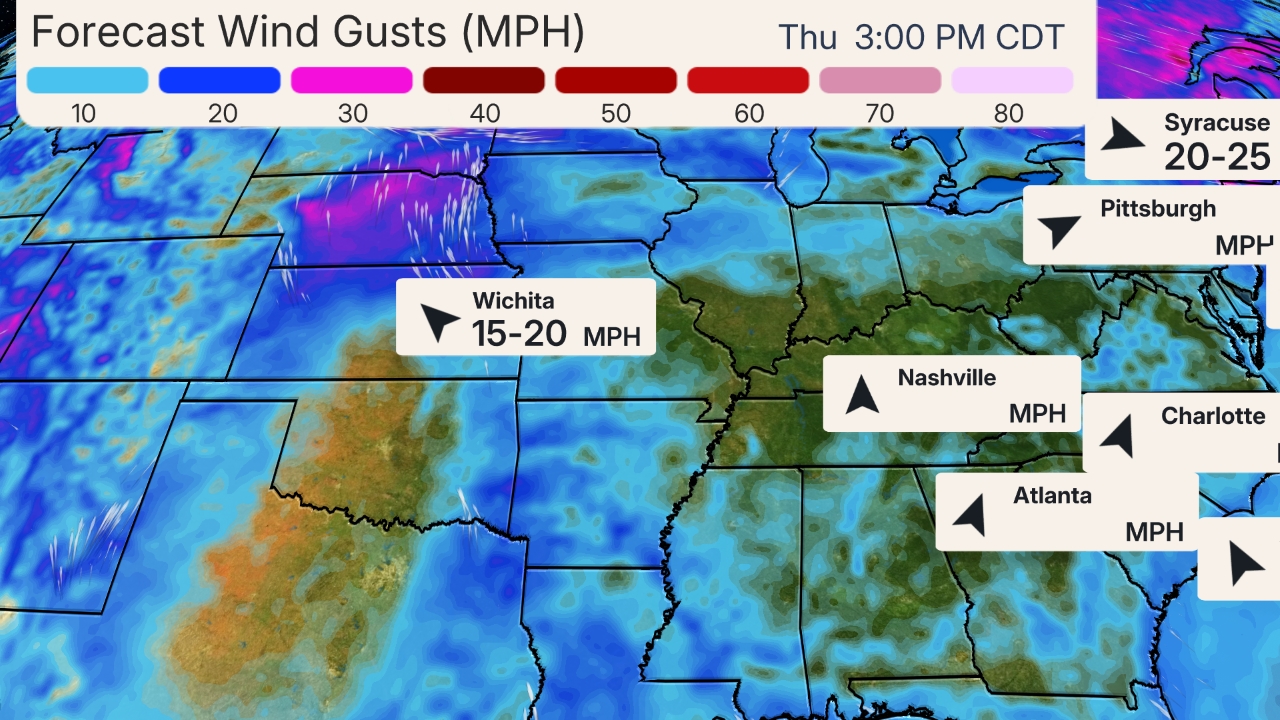

Right now, there’s a broad area of low pressure centered over the southwestern Gulf of Mexico that has become a little better organized as of Thursday morning. This system is already producing winds to near tropical storm force.

Known as a Central American gyre (CAG), this large low-pressure area typically forms both in late spring and early fall. It can spawn tropical storms and hurricanes in both the Atlantic and Eastern Pacific Basins, sometimes in each basin at the same time.

Gulf Development Chance

This area of low pressure has been designated as Invest 96L by the National Hurricane Center.

The low could be designated a tropical or subtropical depression or storm once it has a complete, counterclockwise surface circulation with organized thunderstorms nearby. If it becomes a tropical/subtropical storm, it would be called Nestor.

(MET 101: What is a Subtropical Cyclone)

(The potential area(s) of tropical development according to the latest National Hurricane Center outlook are shown by polygons, color-coded by the chance of development over the next five days. An “X” indicates the location of a current disturbance.)

Regardless of what meteorologists call it, this system is expected to move over the Gulf of Mexico and into the Southeast relatively quickly.

The system may gain some strength, but increasing upper-level winds over the northern Gulf of Mexico, which will help it move swiftly toward the northern Gulf Coast, should also produce wind shear, typically a strike against significant intensification of tropical cyclones.

(Areas of clouds are shown in white. Areas of strong wind shear, the difference in wind speed and direction with height, are shown in purple. High wind shear is hostile to mature tropical cyclones and those trying to develop.)

Potential Impacts

Wind, waves and coastal flood/surge impacts depend on the size and strength of the Gulf system, which remains uncertain given the system hasn’t formed in the Gulf, yet.

South to southwest winds ahead of the system blowing over a long fetch of the Gulf of Mexico may generate swells that may reach the northern and eastern Gulf Coasts as soon as Friday.

These swells could generate high surf and rip currents and could persist through Saturday.

Coastal flooding may become an increasing concern, especially around times of high tide Friday into Saturday, possibly stretching from southeast Louisiana to Florida’s Gulf Coast as far south as Tampa-St. Petersburg or Ft. Myers.

The rainfall forecast, however, is a bit clearer.

This relatively fast movement should keep this from becoming a major, widespread rainfall flood concern. Remember, a tropical storm or hurricane’s rainfall potential largely depends on how fast it moves, not how strong it becomes.

Rain and thunderstorms are expected to arrive along parts of the northern and eastern Gulf Coasts Friday.

This rain could become heavy Friday night into Saturday generally along, and to the northeast of, the track of the Gulf system, and may linger in some parts of the Southeast into Sunday.

Areas from the northern Gulf Coast to Virginia could pick up a few inches of rain. Locally higher amounts are possible where bands or clusters of heavy rain persist for a few hours.

(This should be interpreted as a broad outlook of where the heaviest rain may fall and may shift based on the forecast path of the tropical system. Higher amounts may occur where bands of rain stall over a period of a few hours. )

Overall, this rain could be beneficial, given the flash droughtthat has developed over the Southeast.

This system may then move along the mid-Atlantic coast and may bring rain to the mid-Atlantic and Northeast coast into Sunday night.

Western Gulf Development Unusual This Late

Tropical development in the western Gulf of Mexico is certainly not unusual in hurricane season.

It is quite rare this late in the season, though.

Only seven named storms since 1960 have formed in the western Gulf of Mexico after October 1, according to Brian McNoldy, tropical scientist at the University of Miami.

One of those storms, Tropical Storm Josephine, came ashore in Apalachee Bay, Florida, on Oct. 7, 1996, with maximum winds of 70 mph, just a notch below hurricane status.

Josephine’s most notable impact was storm surge. Storm tides of up to 9 feet were reported in Levy County, Florida. Pinellas and Hillsborough Counties – the Tampa-St. Pete metro area – reported storm tides of 4 to 6 feet that flooded roads and buildings, according to the National Hurricane Center’s report on Josephine.

October tropical storms and hurricanes most often develop in either the western Caribbean Sea, eastern Gulf of Mexico, or off the U.S. East Coast in the western Atlantic Ocean.

(MORE: Hurricane Season is Far From Over)

Roughly 50 percent of Central American gyres have a tropical cyclone associated with them, according to Philippe Papin, research scientist at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory and expert on CAGs. “When a tropical cyclone does occur, it tends to form on the eastern side of the [gyre] and rotates counterclockwise around the larger circulation,” Papin told weather.com.

In recent years, the Central American gyre has spun off some notable storms.

In October 2018, what eventually became Hurricane Michael was spun off the east side of a CAG and was only the fourth mainland U.S. Category 5 landfall.

One year before that, Hurricane Nate also formed along the eastern edge of a CAG and came ashore along the northern Gulf Coast in October 2017. Nate’s deadliest impacts were in Central America, where widespread flooding and mudslides claimed 44 lives.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.