ON BEHALF OF

THE PARLIAMENT AND CITIZENS OF SINT MAARTEN

9 March 2021 Presented by:

The Choharis Law Group, PLLC

1300 19th Street, N.W.

Suite 620

Washington, D.C. 20036 www.choharislaw.com Petitioners, the Parliament and citizens of Sint Maarten (“Petitioners”), respectfully bring to the attention of the Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance (“Special Rapporteur”) and of the Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent (“Working Group”) the persistent acts of racial discrimination and violations of international human rights law by the Kingdom of the Netherlands (“Netherlands”) against Petitioners and others similarly situated in the islands of Aruba and Curaçao as well as in the special municipalities of Bonaire, Sint Eustatius, and Saba—together, the six islands of the former Netherlands Antilles.

For decades, the Netherlands has failed to meet its international legal obligations to promote self-government in, as well as the political, economic, social, and educational advancement of, the islands of the former Netherlands Antilles and to ensure their just treatment and protection against abuses. More recently, the Netherlands has attempted to deny Petitioners and others similarly situated their right to a democratically elected representative government, their right to complete decolonization, and their right to the freedom from racial discrimination and economic and social injustice. Far from providing humanitarian assistance—let alone financial assistance that is commensurate with the funding provided by the Dutch government to its predominantly white, European citizens—the Netherlands is using a global pandemic, economic devastation from two hurricanes, and a global recession to force Petitioners and others similarly situated to surrender their sovereignty and human rights by trying to impose neo-colonial financial, economic, and budgetary authority in place of the democratically elected governments of Sint Maarten, Aruba, and Curaçao. In exchange, the Dutch government is offering yet more debt to these islands conditioned on Petitioners and others meeting fiscal benchmarks that very few countries in the world are currently satisfying. And if Petitioners refuse, the Dutch government has threatened to cut off economic assistance and declare a default on past debt, thereby decimating the credit rating of Sint Maarten and wreaking further economic damage on Sint Maarten’s already precarious economy.

Petitioners respectfully request that the Special Rapporteur and Working Group, with the support and cooperation of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (“OHCHR”), adopt one or more of the following measures and otherwise use its good offices to address and remediate the racial discrimination and human rights violations by the Netherlands against Petitioners: (1) monitor the situation in the islands of the former Netherlands Antilles by means of virtual or actual fact-finding visits; (2) submit an annual report to the Human Rights Council and the General Assembly setting forth findings of human rights violations; (3) promulgate an initial, public report setting forth its preliminary findings on the allegations of racial discrimination and human rights violations by the Netherlands; (4) communicate with the Netherlands regarding its violations of human rights and racial discrimination to make that government aware of its ongoing violations of international law; (5) consider along with counsel for Petitioners strategic litigation in the European Court of Human Rights or other appropriate forum to adjudicate and provide judicial relief for the racial discrimination and human rights violations committed by the Netherlands; (6) advocate and raise public awareness in the Netherlands and in other member states of the European Union (“EU”) regarding the racial discrimination and human rights violations committed by the Netherlands against the governments

Page

and people of the Caribbean islands that are a part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands; (7) formally and publicly urge the Netherlands to cease immediately its human rights violations and racial discrimination; (8) along with the OHCHR, support a process by which Sint Maarten and the other islands of the former Netherlands Antilles may finalize decolonization; and (9) adopt such other measures as the Special Rapporteur, the Working Group, and OHCHR deem necessary and appropriate.

IN SUPPORT OF THIS PETITION, Petitioners state the following:

Jurisdiction of the Special Rapporteur and the Working Group

Pursuant to Human Rights Council Resolutions 7/34 (2008) and 34/35 (24 March 2017) as well as the former Commission on Human Rights Resolutions 1993/20 and 1994/64, the Special Rapporteur has jurisdiction to consider this Petition and the claims of extensive systematic racial discrimination and concomitant violations of international human rights laws committed by the Netherlands.

Pursuant to Human Rights Council Resolutions 9/14 (2008) and 45/24 (1 October 2020) as well as the former Commission on Human Rights Resolution 2002/68, the Working Group has jurisdiction to gather all relevant information relating to the well-being of people of African descent living in Sint Maarten and the other islands of the former Netherlands Antilles and to address the claims of extensive systemic racial discrimination committed by the Netherlands there.

Article 1(1) of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) defines racial discrimination as:

any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, colour, descent, or national or ethnic origin which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life.

This definition encompasses the Dutch government’s violations of international law, attempts to displace a democratically elected government with a neo-colonial fiscal authority appointed by the Dutch government, and grossly unequal economic assistance, especially during a global pandemic following two natural disasters—all based on race, colour, descent, and/or ethnic origin.

FACTUAL ALLEGATIONS OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION AND HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES

As explained below, the islands of Aruba, Sint Maarten, and Curaçao along with the Netherlands are the constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The three island countries enjoy multi-racial, multi-ethnic populations that contribute to the islands’ rich culture and heritage. Although precise statistics on race are not readily available for the islands and the Netherlands, it is clear that on the aggregate level, the Kingdom’s treatment of the overwhelmingly white population of the Netherlands is far superior than its treatment of the people of African descent and other racial and ethnic minorities that comprise the considerable majority of the three Caribbean islands.

Page

Because of a precipitous drop in revenue caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, and two ruinous hurricanes in Sint Maarten in 2017, these three islands are suffering from profound economic devastation. As a result, Sint Maarten, whose population is approximately 85% people of African descent, is extremely vulnerable financially. This vulnerability is manifested in poverty rates, health insurance coverage, and other social welfare barometers that are far below those in the Netherlands, whose population is approximately 80–85 % white. This disparity in economic and social wellbeing has not only existed, but in fact has increased, during the past decade—a period when Aruba, Sint Maarten, and Curacao nominally became “autonomous partners within the Kingdom, alongside the country of the Netherlands” with equal rights and sovereignty.

Most disturbing, the financial vulnerability of the three island countries is being compounded by the Faustian bargain that they were forced to enter by the Dutch government to gain their nominal equality in the agreement that reconstituted the Kingdom of the Netherlands. By means of Boards of Financial Supervision (or in Dutch, Colleges Financieel Toezicht or “CFTs”), financial decisionmaking in Sint Maarten—as well as in Aruba and Curaçao—is controlled by white Dutch fiscal overseers, who continue to impose recessionary budgetary policies during a recession caused by a global pandemic. Not content with beggaring the islands even while the Dutch government props up its own white citizens’ businesses and social safety net (as well as those of other white European nations) with massive government spending, the Dutch government is trying to impose a new financial entity that would further deprive the nominally “equal” island governments of their constitutional authority to formulate budgets, borrow money, and determine local government spending for their own citizens.

And most recently, the Dutch government has demanded that Sint Maarten (1) abandon a bridge loan from an international lender that would have avoided a default with a ten-year old Dutch government loan and (2) abandon recent efforts to finalize their decolonization from the Netherlands. And if Sint Maarten refuses these demands, the Dutch government will deny them the next tranche of a loan and will declare a default of the ten-year old loan—destroying the Sint Maarten economy and the island’s credit rating. Both of these demands are in violation not only of the Kingdom Charter, the constitutional organ of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, but also of the international human rights of the citizens of Sint Maarten, including their right to a democratically elected, representative government and to self-determination. The Dutch government’s blatant attempts to use a global pandemic and economic collapse to reimpose colonial authority over its own, non-European citizens by forcing them to surrender their international human rights—while at the same time approving massive, unconditional government subsidies and financial support for its white, European citizens and even non-citizen, white people in the European Union—constitutes racial discrimination.

Constitutional Overview of the Kingdom of the Netherlands

Sint Maarten is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. After years of wrangling over the post-colonial future of the six Caribbean islands that composed the Netherlands Antilles—namely Aruba, Bonaire, Curaçao, Saba, Sint Eustatius, and Sint Maarten—the Dutch government approved a series of round table conferences beginning in November 2005. Over the course of these round table conferences, the Netherlands, the Netherlands Antillean government, and representatives of the island nations agreed that Sint Maarten and Curaçao would join Aruba and the Netherlands as constitutionally equal “autonomous countries” within the Kingdom of the Netherlands and that Bonaire, Saba, and Sint Eustatius (BES) would become special municipalities of the Netherlands. The Netherlands, further, would assume most of the public debt of the Netherlands Antilles on the condition that the islands accepted outside budgetary oversight and committed to the prevention of future debt buildup through balanced budgets. The closing agreements, known collectively as the 10/10/10 Agreement, were ratified through an Act of Parliament amending the Charter of the Kingdom of the Netherlands (“the Charter”) that the parties signed on September 9, 2010, with an effective date of October 10, 2010.

Political Status of Aruba, Curaçao, and Sint Maarten

The Charter governs the political relationship between the four countries that constitute the Kingdom of the Netherlands.10 As co-equal “autonomous countries,” Aruba, Curaçao, and Sint Maarten are supposed to enjoy full autonomy and to cooperate with the Netherlands on affairs that concern the whole Kingdom.11 Each constituent country has its own government and parliament that are empowered to govern their own affairs.12 All four countries, however, are obliged to “accord one another aid and assistance.”13 The government of each of the Caribbean countries is headed by a governor that represents and is appointed by King Willem-Alexander as the Kingdom head of state.14 The Council of Ministers of the Kingdom, comprised of the twelve to sixteen ministers of the Council of Ministers of the Netherlands and three ministers plenipotentiary of Aruba, Curaçao, and Sint Maarten, governs all Kingdom affairs.15 Kingdom affairs include competence areas that depend on the Kingdom’s singular international legal personality, such as defensive matters, foreign relations, and issues involving Dutch citizenship and nationality.16

Financial Status of Aruba, Curaçao, and Sint Maarten

As noted, the internal fiscal decisionmaking of Sint Maarten—as well as that of Aruba and Curaçao—is controlled by Boards of Financial Supervision, or Colleges Financieel Toezicht (CFTs) in Dutch. CFT Curaçao and Sint Maarten and CFT Aruba are independent Dutch administrative bodies that supervise the public finances of the islands pursuant to the 10/10/10 Agreement and the September 2015 National Ordinance on Aruba Temporary Financial Supervision (LAFT) respectively.17 CFT Curaçao and Sint Maarten consists of four members, including a chairman and three members appointed one each by the Council of Ministers of Curaçao, Sint Maarten, and the Netherlands;18 while CFT Aruba is comprised of three members, including a chairman and two members appointed one each by the Council of Ministers of Aruba and the Netherlands.19 Both CFTs are headed by a single chairman that is appointed by the Prime Minister of the Netherlands and the Council of Ministers of the Kingdom.20 All members of both

http://www.government.nl/News/Press_releases_and_news_items/2010/September/_Constitution al_reform_of_Netherlands_Antilles_completed.

10 STATUUT VOOR HET KONINKRIJK DER NEDERLANDEN [CHARTER] Nov. 17, 2017, art. 1 (Neth.).

11 See supra note 3; id. at Preamble.

12 See id. at arts. 41–42, 46.

13 Id. at art. 36.

14 See id. at art. 2(2). 15 See id. at art. 7

16 See id. at art. 3.

17 See History, supra note 8.

18 RIJKSWET FINANCIEEL TOEZICHT CURAÇAO EN SINT MAARTEN [KINGDOM ACT OF 7 JULY 2010] arts. 2(2)–(3) (Neth.).

19 LANDSVERORDENING ARUBA FINANCIEEL TOEZICHT [L.A.F.T. OF 31 AUG. 2015] arts. 3(1)–(2) (Neth.).

20 See id. at art. 3(2)(a); KINGDOM ACT OF 7 JULY 2010 at art. 2(3)(a).

CFTs are white and of Dutch-origin. The primary de jure function of the CFTs is to scrutinize the adopted budgets against the agreed standards, namely the financial balancing norm.

The international financial status of Aruba, Curaçao, and Sint Maarten, meanwhile, is governed by several provisions of the Charter. Pursuant to Article 25 of the Charter, the King may not bind the Caribbean island countries to international economic and financial agreements and it may not terminate such agreements except with the acquiescence of their governments. The Kingdom government, moreover, is duty bound to assist in the conclusion of an international economic or financial agreement that is desired by the governments of Aruba, Curaçao, or Sint Maarten, if not inconsistent with their Kingdom ties. And the Netherlands is obliged to lend money to Sint Maarten to cover its expenditures under the same terms it borrows. Nevertheless, pursuant to the 10/10/10 agreement, Sint Maarten must get the consent of the CFT before seeking access to the financial markets.

Hurricane Irma and the COVID-19 Pandemic

The economy of Sint Maarten, as a small Caribbean island state, was particularly vulnerable to the impact of the Coronavirus pandemic. Sint Maarten’s economy is heavily dependent on tourism revenue, with related sectors accounting for up to 45% of Sint Maarten’s GDP. Amid the global pandemic, however, international tourism has nearly come to a halt and periodic lockdowns and other preventive measures have impacted even local consumption. As a result, Sint Maarten’s economy is projected to contract by 25%.28

To make matters worse, the economy of Sint Maarten was still struggling to recover from the disastrous 2017 hurricane season. Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017 destroyed or seriously damaged 90% of the structures on Sint Maarten and caused as much as $3 billion in damages and losses. In the aftermath of this devastation, Sint Maarten’s economy contracted by a cumulative 12% as tax revenues declined and government spending increased to rebuild public infrastructure. The Netherlands promised $654.5 million (€550 million) in aid to help with the post-hurricane reconstruction on Sint Maarten, but over half of the money—$559.3 million (€470 million) of which is held in a public trust managed by the World Bank—remains unallocated and only $90.3 million (€75.9 million) has been disbursed. The need far outweighs the promised funds, however, with total recovery estimated to cost $2.3 billion. Disbursements to and from the Trust Fund must be approved by the Dutch Parliament and State Secretary for the Interior and Kingdom Relations. To date, the disbursements have focused on infrastructure reconstruction, housing repair, and capacity building.34 Even when the Dutch Parliament and State Secretary come to an agreement with local officials on a particular project, such as airport reconstruction, long negotiations and approval delays often hinder progress. But according to a 2018 report by the Dutch Court of Audit, the parties often differ over the scope of the recovery plan with the Dutch State Secretary often rejecting a number of technical assistance requests from Sint Maarten because he did not believe they were “directly related to the reconstruction work.” With such a slow disbursement rate, the Sint Maarten agency that oversees the implementation of recovery activities is already negotiating an extension of the December 2025 deadline for fear that the full trust fund will not be utilized for its promised purpose.

But whatever the reasons for the Dutch government’s rejection of specific funding needs, one thing is beyond dispute: The onerous funding process that the Netherlands has erected— including its veto authority over every penny requested—has resulted in the ongoing deprivation of a vast amount of relief assistance that was promised to the citizens of Sint Maarten. And as explained below, instead of disbursing this promised relief aid quickly now that Sint Maarten has been battered by a second natural disaster (the COVID-19 pandemic) and resulting economic distress, the Dutch government continues to withhold it. Instead, the Netherlands has required its citizens in Sint Maarten to assume ever greater amounts of debt. Other than with its own Caribbean islands, we are not aware of anywhere else in the Kingdom, in Europe, or in other countries where the Dutch government has withheld emergency relief aid and imposed unsustainable debt instead. Worse still, we are unaware of anywhere else where the Dutch government required the surrender of democratic rights in order to receive such debt or aid of any kind.

History of Dutch Discrimination Against Caribbean Islands

There is a long history of discrimination, particularly evident in the award of social benefits, against the mostly Black Dutch citizens in the Caribbean part of the Kingdom as compared to the Dutch citizens in the European part. As a collection of Dutch NGOs observed in their recent report to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD):

[T]he Dutch legislature has a discretion to differentiate between the BES islands and the European Netherlands when the size of the islands, geographical circumstances, climate or other factors permit. The legislature uses this discretion to justify unequal rights to social welfare, which has led to (social) disparities between the BES islands and the European Netherlands. Such disparities have especially affected residents of these islands who, because of enduring racism, are often thought to be essentially distinct peoples from Dutch Europeans.

As an example of this social welfare disparity, all citizens of the constituent country of the Netherlands—regardless of income levels—are entitled to receive a quarterly child allowance, but the benefit was only extended on a monthly basis to citizens living in the Caribbean municipalities in 2016. Even still, Dutch citizens living in Bonaire receive $1,224 per child per year and Dutch citizens living in Saba and Sint Eustatius received $1,248 per child per year, while Dutch citizens living in European municipalities receive up to $1,500 per child per year depending on the child’s age. There is a similar difference of over $500 per year in the retirement benefits afforded to the elderly on the BES islands and on Sint Maarten compared to what is afforded to the elderly in the Netherlands, equivalent to a disparity of 41-42% and 51% respectively.

These disparities are especially egregious considering that the cost of living is almost twice as high on the islands44 and the tax rates are comparable or higher.

There is no serious dispute that these social and economic disparities are the result of “enduring racism” in the words of the Dutch NGO report to the CERD. During a November 2020 interview, a Dutch Member of Parliament who is on the Kingdom Relations portfolio was similarly frank about the poverty stemming from a denial of the islanders’ human rights. Referring to Bonaire, she reported that, “Poverty is shocking. But the islands are seen as a small part. And how do you tackle poverty? As an MP, you have to look for a hook in the beginning and for me that is: poverty from human rights.” She was also candid about the longstanding history of racial discrimination again

st the islanders reaching back to slavery: “I have always dealt with issues of discrimination and equality. And the history of slavery also needs to be put on the map.” Finally, the MP admitted that the Dutch’s government’s ostensible adherence to human rights does not extend to its island citizens. “Well, what really stays with me is that in the beginning I was more or less scorned in the Chamber. ‘Because in the Netherlands human rights are well regulated!’ That is not the case. Only when you start listing all the things you see or read there on the island, will something change.”

Moreover, the Netherlands has a history of undermining the public participation rights of Dutch citizens on the BES islands. Not only did the 10/10/10 constitutional reform proceed against the overwhelming disapproval of Sint Eustatius,50 but the Netherlands has continued to discriminate against the special municipality of “Statia” by intervening in its local politics and governance in a way that it has never done with the European municipalities of the Netherlands. In February 2018, the Dutch Government removed the Island Council, the Executive Council, and the Governor for alleged “neglect of duties” and installed a Government Commission led by appointed European Dutch politicians. The Dutch decapitation of the Statian executive branch bypassed the island’s political process, with elections being postponed from 2019 until 2021. The move also came after the elected leaders on the island had pushed for greater autonomy and independence. The Dutch State Secretary accused the Sint Eustatius administration of “lawlessness, financial mismanagement, discrimination and intimidation” on the basis of a report issued by a committee of wisemen that was unilaterally appointed by the Dutch government in the aftermath of the 2017 hurricanes. The accusations ignored the limited authorities of the elected Statian government whose public expenditures were all subject to the scrutiny of an independent auditor, namely the BES Board of Supervision or CFT BES in Dutch. Again, the predictable result of the Dutch government’s ongoing denial of Statia’s right to self-government has been deplorable living conditions, such as tap water that is not potable for the vast majority of islanders despite the Dutch government’s overseer running the island for nearly three years.

Not only are the actions of the Dutch government consistent with their colonial past and recent history in the former Dutch Antilles, but they align with the pervasive racism and xenophobia that have permeated Dutch politics in recent years. For instance, the CERD investigated the Netherlands over its “Black Pete” cultural practice, which usually sees actors portraying the figure—who is “a fool and…a servant of Santa Claus”—dressed in black face and stereotyping people of African descent. CERD described the practice in a 2015 report as a “vestige of slavery … [and] injurious to the dignity and self-esteem of children and adults of African descent.” Despite CERD’s admonitions and negative public attention to the practice around the world, however, the cultural practice remains to this day.

Beyond ethnic stereotypes and more recently, the Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Racism also found in 2019 that:

The reality [in the Netherlands] therefore seems to be one in which race, ethnicity, national origin, religion and other factors determine who is treated fully as a citizen. To be more specific, in many areas of life – including in social and political discourse, and even in some laws and policies – different factors reinforce the view that to truly or genuinely belong is to be white and of Western origin.

In fact, the Dutch government recently collapsed over a scandal involving false allegations of fraud made by the Dutch Tax and Customs Administration that wrongfully denied childcare benefits to an estimated 26,000 parents between 2013 and 2019. The allegations first emerged in September 2018 when journalists accused the government of racial profiling, and the tax authority subsequently admitted that many families were subjected to special scrutiny because of their ethnic origin or dual nationalities. The Dutch government was forced to resign, however, after a December 2020 report from a parliamentary committee of inquiry found “unprecedented injustice” and violations of “fundamental principles of the rule of law.” Yet in the islands of the former Netherland Antilles, such rampant discrimination for decades has seemed to escape Dutch media attention and parliamentary scrutiny.

Caribbean Entity for Reform (COHO) and Development

In response to requests by Curaçao, Aruba, and Sint Maarten for additional Coronavirusrelated relief, the Government of the Netherlands instead proposed the creation of an independent Dutch administrative body, the Caribbean reform entity known as the Entity for Reform and Development (“COHO” in Dutch). While the statute has not yet been finalized, the proposed law provides for the Dutch Minister of The Interior and Kingdom Relations to appoint the three members of the COHO, which will be based thousands of miles away “in The Hague.” The COHO will oversee sweeping economic reforms and will enjoy legislative input in the three island countries. Predicated on a purported need for budgetary and governance reforms, the COHO will control a wide range of government functions, including “(a) the public authorities; (b) finances; (c) economic reforms; (d) healthcare; (e) education; (f) strengthening the rule of law; and (g) infrastructure” on each of the three islands for a minimum of six years. Nor is the COHO’s governmental authority limited to administrative functions. Rather, as explained in the draft legislation’s appended Explanatory Memorandum, COHO “experts” will draft implementing legislation for passage by the island legislatures:

The concept of support also includes the use of expertise. If the entity [COHO] itself has the necessary expertise, it can provide the requested support itself, but it is also possible that the entity will hire the necessary expertise. This could include legislative capacity. If one of the countries needs support in drafting legislation, the entity [COHO] can, if it has legislative lawyers, make this capacity available. If the entity does not have legal counsel, it may, depending on the necessary expertise, request the Dutch Minister to appoint experts (Article 18). These experts shall be responsible, insofar as they assist the Caribbean reform entity [COHO] in carrying out its duties. Furthermore, it is conceivable that the entity [COHO] will hire the necessary expertise externally.

If the COHO decides that the island governments are not fulfilling their reform obligations (i.e., do not “comply” with the COHO’s demands, in the words of the Explanatory Memorandum), it may institute enhanced “financial supervision” under standards established by the relevant CFT. Worse, the unelected COHO may suspend aid to the island in whole or in part. As Section 3.7.1 of the Explanatory Memorandum makes clear:

The provision of these funds is not without obligation. It is done under the general condition that Aruba, Curaçao and Sint Maarten make efforts to comply with their various specifications under the state law and the [respective] country’s packages [which will set forth greater details regarding reform obligations]. If a[n island] country fails to make this effort and obligations are structurally not fulfilled, the Netherlands must have an emergency brake to suspend or even stop the provision of financial resources.

So in the future, despite paying national taxes and despite being forced to surrender substantial parts of their administrative and legislative sovereignty to the COHO, the island citizens may still be deprived of future funding if the COHO sees fit. As explained below, this Dutch threat of economic destruction of the islands is not new.

The Dutch government demanded this thraldom despi

te hundreds of millions of dollars of unspent hurricane relief funds for Sint Maarten languishing in the World Bank trust fund. The proposed COHO legislation and Explanatory Memorandum are completely silent about the availability of these funds—disbursement of which does not require Sint Maarten to surrender its sovereignty—rendering the proposed legislation and accompanying Explanatory Memorandum morally as well as factually deficient.

Moreover, the Netherlands’ pretext that such extreme measures are necessary because of financial mismanagement by Sint Maarten’s government is further belied by the fact that the economic situation on the island remains under the absolute supervision of the CFT. Further undermining the COHO draft legislation, the supporting Explanatory Memorandum cites a single report about the reasons underlying the islands’ economic circumstances to justify the COHO’s

displacement of the elected island governments.77 But of course, no evidence or circumstance can justify the Netherlands’ denying its island citizens their basic human rights, including the right to a full measure of self-governance.

After proposing the COHO, the Netherlands moved to force the islands into accepting it. The Governments of Aruba and Curaçao79 assented to the COHO in exchange for €105 million and €50 million respectively in interest-free loans. Sint Maarten tried to retain its sovereignty and entered into extensive negotiations with the Dutch.80 But when Sint Maarten secured outside financing so that it would not remain dependent exclusively on the Netherlands for refinancing and liquidity, the Netherlands forbid Sint Maarten from proceeding with the loan. In October 2020, CFT Curaçao and Sint Maarten chided the government of Sint Maarten for attempting to procure a loan from the capital markets through a public bond issuance. Shortly thereafter, on October 20, 2020, the Dutch State Secretary for the Interior and Kingdom Relations, Raymond Knops (“Knops”), sent a letter to the Sint Maarten Minister of Finance, A. Irion, threatening to declare a decade-old loan in default unless Sint Maarten abandoned the new source of financing. Specifically, Knops wrote:

As you know, a bullet loan of ANG 50 million [US $28,000,000] from the

Netherlands to Sint Maarten will expire on 21 October 2020. For ten years it has

77 The Explanatory Memorandum (Section 1.2) explains the economic problems confronting the island countries and their causes in the following manner:

[T]he countries lagged behind the development of the world economy, Latin America and the Caribbean region. Meanwhile, the debt ratios of all three countries rose sharply. The lagging economic performance has a structural character in addition to incidental and external causes (Venezuela, ISLA refinery, hurricanes). The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has observed for years that the rigid labour market and the unfavourable business environment in the countries are a barrier to economic growth and that the high costs of the public sector are too heavy a financial burden. There is also insufficient connection between education and the labour market, high and rising costs, and increasing risks in the financial sector. been known to Sint Maarten that this loan has to be repaid. Although I of course have understanding for the fact that the effects of Hurricane Irma have required a great deal of your attention and energy in recent years, this does not diminish this payment commitment, to which the CFT has also repeatedly drawn your attention.

Knops made no mention of the COVID pandemic, the threat to the public health of the people of Sint Maarten who are his fellow Dutch citizens, or the economic devastation resulting from the near-total loss of tourism revenue. Nor did he mention the hundreds of millions of untapped hurricane relief funds still available in the World Bank trust. Instead, he affirmed that the unelected CFT, over which the Sint Maarten government had no authority, could block Sint Maarten from obtaining funding to refinance the loan on its own: “On September 17th, last, you submitted a loan request to the CFT for refinancing of this loan [from the capital markets]. The CFT was not in agreement with this proposed loan request and has indicated that decision-making on this request should take place in the Kingdom Council of Ministers (CFT 202000132).” The CFT blocked Sint Maarten from attaining the loan despite Sint Maarten’s clear right to obtain such financing under Article 26 of the Kingdom Charter: “If the Government of Aruba, Curaçao or St Maarten communicates its wish for the conclusion of an international economic or financial agreement that applies solely to the Country concerned, the Government of the Kingdom shall assist in the conclusion of such an agreement, unless this would be inconsistent with the Country’s ties with the Kingdom.”

Far from opposing the CFT and protecting Sint Maarten’s rights under Article 26, Knops proceeded to threaten Sint Maarten if it tried to proceed with funding independent of the Dutch government’s COHO scheme. First, Knops offered a mere “four-week extension” of the loan “in order to prevent a technical default on the part of Sint Maarten, with all its consequences.” By that, he meant that a Dutch declaration of default on the ten-year old bond would trigger crossdefault provisions on all of Sint Maarten’s debt (such provisions are common in loan agreements). This cascade of loan defaults would crater Sint Maarten’s credit rating and eliminate the possibility of debt financing when needed most to protect the people of Sint Maarten from the Coronavirus threat and economic turmoil—a prospect Knops taciturnly termed, “all its consequences.” During that four weeks period, Knops continued, Sint Maarten must “meet the conditions attached to the second tranche of liquidity support” under the COHO scheme. And if Sint Maarten is obedient— “if you comply” in Knops words—“our countries can discuss the third tranche of liquidity support . . . [and] a longer-term solution to the expiring [ten-year old] loan.”

The Dutch government’s strategy could not be clearer: continue to keep Sint Maarten (as well as Aruba and Curaçao) indebted through a never-ending cycle of debt owed to the Dutch government, and only to the Dutch government, by barring Sint Maarten and its sister islands from accessing other sources of funding and then continuing to demand that the islands abdicate ever greater parts of their sovereignty, even those expressly guaranteed in the Kingdom Charter, as the price of that debt. Knops makes this 21st century peonage clear:

However, this goodwill on my part will expire if you continue to seek a domestic loan for which no approval has been obtained from the CFT.

I am referring, of course, to the prospectus that the CBCS [Central Bank of Curaçao and Sint Maarten] published on October 14th last for a domestic bond of ANG 75 million [US $ 42,000,000] for the country Sint Maarten. The CFT informed you on October 12th last, that by floating this bond, you are acting in violation of Article 16 of the Rft [Kingdom Law on Financial Supervision of Curaçao and Sint Maarten] (CFT 202000143).

I therefore call on you to, in accordance with the letter from the CFT, cease the procedure which you started . . . .

Unable to risk the destruction of its credit—especially amid a global pandemic and recession—

Sint Maarten capitulated and withdrew its bond offering.

Unbowed, on November 5, 2020, Petitioner the Parliament of Sint Maarten passed a motion that inter alia authorized “the Parliament and Government of Sint Maarten [to purse] ending the violations of Sint Maarten’s UN-mandated right to a full measure of self-government; completing the decolonization of Sint Maarten and the other islands of the former Netherlands Antilles with the assistance of the United Nations in accordance with the past, present, and future obligations of the Netherlands under international law; and obtaining reparations from the Netherlands for violations of international law and norms as well as its treaty obligations.”84 That motion authorized the preparation and filing of this Petition among other things.

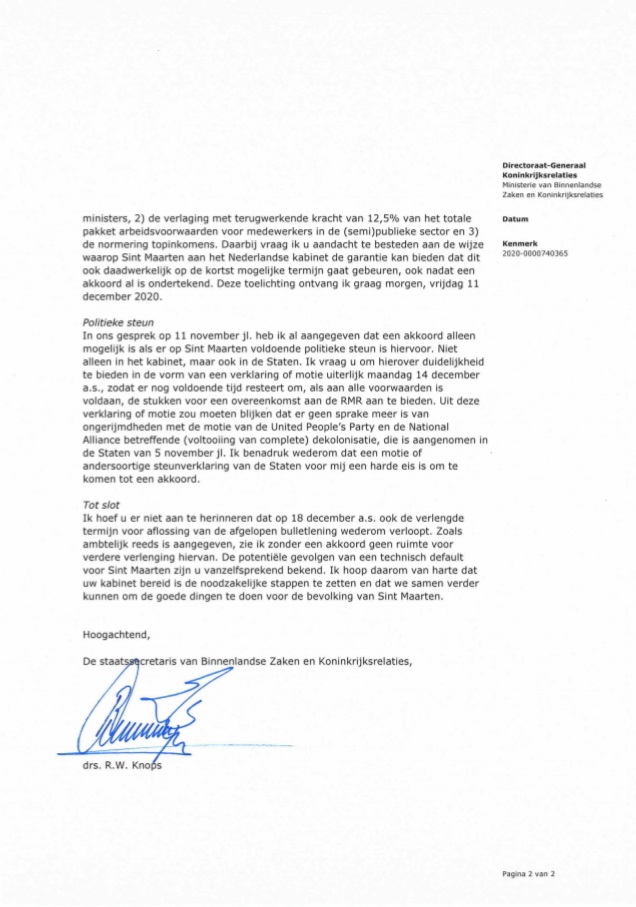

In response, on December 10, 2020, Knops wrote another letter, this time to the Prime Minister of Sint Maarten, Silveria Jacobs. After demanding an explanation of how the Sint Maarten government would implement recessionary slashing of government expenditures “in the shortest possible time,” Knops then demanded a

declaration or motion [to] show that there are [sic] no more incongruousness with the motion of the United People’s Party and the National Alliance on (completion of complete [sic]) decolonization, which was adopted in the States of 5 November last. I stress once again that a motion or other kind of declaration of support by the States is a firm demand for me to reach an agreement.

As explained below, this demand—that Sint Maarten abandon its right to seek redress from the U.N. Special Rapporteur and Working Group for the Dutch government’s deprivations of its island citizens’ human rights as the price of additional loans—itself violates international law and constitutes a modern-day form of debt slavery.

Knops concluded with a return to the prospect of a loan default (and the disastrous economic consequences) if Sint Maarten did not obey: “Finally, I do not need to remind you that on December 18th, the extended deadline for repayment of the last bullet [ten-year old] loan will also expire again. As has already been indicated, I do not see any scope for further extension without an agreement. The potential consequences of a technical default for Sint Maarten are obviously known to you.”

On December 14, 2020, Prime Minister Jacobs announced that her government had agreed to “structural reforms” and other measures as required by the COHO scheme in exchange for a third tranche of liquidity funding. The Prime Minister’s explanation for why she had acceded to the terms of the COHO proposal was clear: “As a country, we are between a rock and a hard place . . . weighing our strive [sic] for autonomy against the immediate needs of the people of St. Maarten. Large countries around the world are faced with financial challenges, but our situation is one that is exacerbated by the challenges [two hurricanes] we recently faced in 2017 and the subsequent slow recovery and improvement in our effectiveness and efficiency as a government. My personal feelings aside, I m

ust put the needs of the country as my highest priority.”86

Dutch Discrimination in Context

The discrimination by the Dutch government against its own island citizens becomes undeniable when the COHO’s scheme of recessionary, balanced-budget policies that will ensure the islands’ ongoing indebtedness to the Netherlands, coupled with the Dutch government’s imposition of neo-colonial authority over the islands, are contrasted with the Dutch government’s actions towards its European citizens and those of other EU nations.

The Netherlands has only enjoyed a budget surplus since 2017 and has posted an average debt-to-GDP ratio of over 60% in the last ten years, having been above EU targets for six of the last ten years.87 Meanwhile, the Government recently announced €11 billion in additional support for businesses and employees in the Netherlands,88 in addition to two previous stimulus packages

86 Press Release, Prime Minister Silveria Jacobs Updates Parliament on 3rd Tranche of Liquidity

Support Agreements with BZK, GOV’T OF SINT MAARTEN (Dec. 14, 2020),

http://www.sintmaartengov.org/PressReleases/Pages/Prime-Minister-Silveria-Jacobs-updatesParliament-on-3rd-tranche-of-liquidity-support-agreements-with-BZK.aspx.

87 See Netherlands Government Budget, TRADING ECONOMICS,

https://tradingeconomics.com/netherlands/government-budget (last visited Mar. 2021);

Netherlands Government Debt to GDP, TRADING ECONOMICS, https://tradingeconomics.com/netherlands/government-debt-to-gdp (last visited Mar. 2021). 88 Press Release, Government Extends Coronavirus Support for Jobs and the Economy into 2021,

GOV’T OF THE NETH. (Aug. 28, 2020), https://www.government.nl/latest/news/2020/08/28/government-extends-coronavirus-supportfor-jobs-and-the-economy-into-2021.

totally €20 billion and €13 billion. In July, the Dutch Government also agreed to €750 billion in EU Coronavirus-related relief, split nearly evenly between grants and loans, for southern EU member states without forcing recipient states to meet artificial fiscal or budgetary benchmarks. Following the Beirut explosion, the Netherlands committed €1 million to the Lebanese Red Cross and made another €3 million available to various Dutch aid organizations responding to the disaster—without any demands for budgetary or other governmental reforms by the Lebanese government. And the European Commission—with the support of the Dutch Government— pledged over €60 million in unconditional humanitarian assistance to Lebanon—again without any Dutch demands for budgetary or other reforms by the Lebanese government.

Deprivation of Human Rights

There are numerous sources of international law applicable to the Netherlands that set forth: protections for populations which have not achieved full self-determination, the right to equality under the law and non-discrimination, and the right to meaningful political participation and self-governance. While there may be debate about some of them regarding their binding nature and means of enforceability, there can be no debate that at a minimum they set forth broad principles of international law to which the Netherlands continues to claim adherence and which arguably codifies customary international law.

International Treaties and Instruments

Under the United Nations Charter, Ch. XI, Article 73, member states “recognize the principle that the interests of the inhabitants of these territories are paramount, and accept as a

sacred trust the obligation to promote to the utmost . . . the well-being of the inhabitants of these territories.” Similarly, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) provides that “All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law” (Art. 7) and that the “will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government; this will shall be expressed in periodic and genuine elections” (Art. 21). The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), Article 1, provides that “States Parties to the present Covenant, including those having responsibility for the administration of Non-Self-Governing and Trust Territories, shall promote the realization of the right of self-determination, and shall respect that right, in conformity with the provisions of the Charter of the United Nations.” Article 25 guarantees the right to political participation, which must be meaningful, and Articles 2, 3, and 26 prohibit discrimination and guarantee equal protection of law. This list of international legal instruments is not exhaustive.

Similarly, European treaties may also provide a basis for Sint Maarten’s legal claims.

These would include the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental

“Members of the United Nations which have or assume responsibilities for the administration of territories whose peoples have not yet attained a full measure of self-government recognize the principle that the interests of the inhabitants of these territories are paramount, and accept as a sacred trust the obligation to promote to the utmost, within the system of international peace and security established by the present Charter, the well-being of the inhabitants of these territories, and, to this end:

a. to ensure, with due respect for the culture of the peoples concerned, their political, economic, social, and educational advancement, their just treatment, and their protection against abuses;

b. to develop self-government, to take due account of the political aspirations of the peoples, and to assist them in the progressive development of their free political institutions, according to the particular circumstances of each territory and its peoples and their varying stages of advancement; c. to further international peace and security;

d. to promote constructive measures of development, to encourage research, and to cooperate with one another and, when and where appropriate, with specialized international bodies with a view to the practical achievement of the social, economic, and scientific purposes set forth in this Article; and

e. to transmit regularly to the Secretary-General for information purposes, subject to such limitation as security and constitutional considerations may require, statistical and other information of a technical nature relating to economic, social, and educational conditions in the territories for which they are respectively responsible other than those territories to which Chapters XII and XIII apply.” (emphasis added).

Freedoms, better known as the European Convention on Human Rights, which includes Article 14 (prohibition against discrimination) and Protocol 1, Art. 3 (right to free elections).96 Moreover, while application of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU)97 to Sint Maarten as one of the overseas countries and territories (“OCTs”) would seem to be restricted to Part 4,98 the Overseas Association Decision Council also opined that “the special relationship between the Union and the OCTs should move away from a classic development cooperation approach to a reciprocal partnership;”99 “the solidarity between the Union and the OCTs should be based on their unique relationship and their belonging to the same ‘European family”;100 and the “Union recognizes the importance of developing a more active partnership with the OCTs as regards good governance . . . .”101

United Nations General Assembly Resolutions

Although international law generally does not accord UN General Assembly Resolutions the same status as other authorities, there are several UNGA resolutions that are relevant, including Resolution 742 (1953) (factors regarding attainment of self-governance) and Resolution

96 The Communication contained in a note verbale from the Permanent Representation of the Netherlands, dated 27 September 2010, registered at the Secretariat General on 28 September 2010, provides among other things that:

The Kingdom of the Netherlands will accordingly remain the subject of international law with which agreements are concluded. . . . The agreements that now apply to the Netherlands Antilles will also continue to apply to these islands [Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba]; however, the Government of the Netherlands will now be responsible for implementing these agreements.

97 The TFEU provides in Part IV (Art. 198):

The Member States agree to associate with the Union the non-European countries and territories which have special relations with Denmark, France, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. These countries and territories (hereinafter called the ‘countries and territories’) are listed in Annex II.

The purpose of association shall be to promote the economic and social development of the countries and territories and to establish close economic relations between them and the Union as a whole.

In accordance with the principles set out in the preamble to this Treaty, association shall serve primarily to further the interests and prosperity of the inhabitants of these countries and territories in order to lead them to the economic, social and cultural development to which they aspire.

98 See Council Decision 2013/755/EU, ¶ 4 (25 Nov. 2013) (“Overseas Association Decision”) (holding that the “TFEU and its secondary legislation do not automatically apply to the OCTs” and that the OCTs “must comply with the obligations imposed on third countries in respect of trade”).

99 Id. at ¶ 5.

100 Id.

101 Id. at ¶ 20.

Page

945(X)(1955) (opinion that it is appropriate for the Netherlands to cease providing information about the former Netherland Antilles under UN Charter Art. 73(e)). We emphasize that Resolution 945(X) was on its face limited to relieving the Dutch government from its reporting requirement under Article 73(e). Resolution 945(X) did not even address, let alone affirmatively relieve, the Dutch government of the rest of its obligations under Article 73 (a)-(d). In fact, it is arguable that the Dutch government is in violation of a subsequent resolution that imposed reporting requirements under some circumstances.

Customary International Law

The International Court of Justice in the February 2019 Chagos Island case affirmed that the right to self-determination is a legal obligation under international law. In doing so, the ICJ relied heavily on UNGA Res. 1514 (XV) (1960), which the ICJ called a defining moment in decolonization. As discussed above, that Resolution calls for immediate steps toward selfdetermination and rejects lack of preparedness as a pretext for colonialism.

International legal scholars have been at the forefront of arguing that customary international law affords OCTs additional rights of self-governance, equal treatment, and nondiscrimination from which the former colonial powers may not derogate. For example, with respect to Sint Maarten and similarly situated OCTs, some scholars argue that “the EU law of the Overseas” countries and territories extends rights established in other parts of the Treaty of the Functioning of the EU (“TFEU”) to OCTs as well. Based on this premise, many of the TFEU’s provisions and protections should apply to Sint Maarten and other similarly situated OCTs irrespective of the Overseas Association Decision. These would include Art. 18 (barring discrimination based on nationality); Art. 20 (rights of EU citizenship); Art. 22 (right to vote and stand as a candidate in municipal elections); and perhaps Art. 24 (citizens’ initiatives).

More generally, over the last quarter century, there has been an explosion of legal scholarship seeking to establish an international legal right to exercise democratic governance, beginning with the seminal work of Thomas Franck. This body of scholarship posits not only that democratic governance is becoming the exclusive source of legitimacy for governments under

international law, but also that there is an emerging international human right to be governed by state authorities that have been formed through democratic processes.

Finally, there is substantial legal authority for the proposition that the EU itself, as well as its Member States, are subject to customary international law that would include antidiscrimination protections, among others.

The Human Toll from Years of Human Rights Violations

Not surprisingly, the long history of Dutch human rights violations in the former Netherland Antilles has resulted in stark differences between the health and welfare of white, European Dutch citizens and the majority non-white / people of color Dutch citizens of the Caribbean islands, including Sint Maarten. The following are a few additional examples:

The prison conditions in Aruba, Curaçao, and Sint Maarten are the subject of scrutiny by several international organizations. Amnesty International has reported generally appalling conditions in asylum detention centers in particular, including “overcrowding, a lack of privacy, poor hygiene in shower and bathroom areas, and a lack of suitable bedding.” The Council of Europe’s Committee for the Prevention of Torture has put in place enhanced supervision procedures in the islands since 2015 because the prison conditions do not meet the standards of the European Court of Human Rights. The island governments have also permitted independent monitoring by the International Committee of the Red Cross, the UN Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture, and the UN Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent. In addition to the pre-existing challenges with the prison conditions, nearly half of Sint Maarten’s prison cells have been deemed unsuitable since they were damaged by Hurricane Irma, so the government has taken to transferring dozens of prisoners to the Netherlands. This practice not only draws on Sint Maarten’s already limited resources for post-hurricane reconstruction and coronavirus relief, but it also deprives prisoners of access to their families as required under international standards. Again, the Dutch government has sought $15 million to enhance the Public Prosecutor’s Office, who is appointed by the Netherlands government, but no funds have been designated to improve the dilapidated prisons that enhanced prosecutions would presumably further overcrowd.

As another example, while budgets for public education are not reported the same in Sint Maarten and the Netherlands—making direct comparisons difficult—roughly speaking the national budget allocation in Sint Maarten’s Ministry for Education, Culture, Youth and Sports in 2019 equaled $70 million (ANG 123,677,186),113 while Dutch expenditures in 2019 totaled $43.2 billion (€79.7 billion) for education, culture and science.114 This works out to roughly $9,508 per student in Sint Maarten115 compared to roughly $15,341 per student in the Netherlands.

Public disclosures for the healthcare and other social welfare budgets of Sint Maarten and the Netherlands are also not reported the same. However, it appears that the entire 2019 budget for the Sint Maarten Ministry of Health, Social Development and Labor Affairs was $ 36.7 million (ANG 64,782,192), which equals approximately $901 per person.117 Meanwhile, Dutch government expenditures in 2019 totaled $89.4 billion for healthcare alone, which amounts to about $5,159 per person. The healthcare systems in Sint Maarten and the Netherlands are both privately managed, with government oversight; but while Sint Maarten has primary and secondary health services, patients requiring complex care services generally must seek treatment outside of Sint Maarten. With an estimated 30% of the population uninsured and high general poverty rates, these services may be unattainable for many on Sint Maarten. Dutch citizens, meanwhile, enjoy universal health insurance and one of best health care systems in the world.

Appointments Aruba, Sint Maarten and the BES-Islands, GOV’T OF THE NETH. (Oct. 8, 2010), https://www.government.nl/latest/news/2010/10/08/judiciary-appointments-aruba-sint-maartenand-the-bes-islands.

113 See LAND SINT MAARTEN: ONTWEPBEGROTING DIENSTJAAR 2020 [SINT MAARTEN: DRAFT 2020 BUDGET], at 40 (on file with Petitioners’ counsel) (calculated using a 2019 exchange rate of: 1 ANG = 0.56646 USD).

114 See SUMMARY OF THE 2019 BUDGET MEMORANDUM, GOV’T OF THE NETH. 6 (2020) (calculated using a 2019 exchange rate of: 1 EUR = 1.1220 USD).

115 See Sint Maarten (Dutch Part): Education System, UNESCO, http://uis.unesco.org/country/SX (last visited Mar. 2021) (calculated by the pre-primary, primary, and secondary student populations).

These deprivations resulting from Dutch discriminatory policies and spending have had predictable and tragic consequences. The average life expectancy at birth on Sint Maarten in 2012 was 77.1 years for women and 69.2 years for men, whereas the average life expectancy at birth in the Netherlands in 2012 was 83 years for women and 79.3 years for men —a difference of over 7% for women and nearly 15% for men. As a further example, according to the Sint Maarten Anti-Poverty Platform, at least 94% of households on the island live in poverty with a household income of less than $2,222 per month as of 2015. This was an increase of 19% in the first five years after the 10/10/10 Agreement. The 2017 hurricanes and the financial impact of the Coronavirus have devastated Sint Maarten’s economy, with unemployment projected to increase by over 16% in the coming year, so poverty rates on the island will almost certainly worsen before they improve.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth above, Petitioners respectfully request that the Special Rapporteur and Working Group provide the relief requested in the Petition and conduct fact-finding missions to investigate the claims set forth herein concerning human rights violations and racial discrimination committed by the Netherlands; issue an interim report followed by an annual report concerning its fact finding; engage the public in the Netherlands and other EU member states on its fact finding; formally and publicly urge the Netherlands to cease immediately its human rights violations and racial discrimination, including but not limited to (i) ending the forced surrender of human and democratic rights for any reason, (ii) ending the imposition of additional debt and replacing it with grants and similar kinds of relief that are available to Dutch citizens in the Netherlands, (iii) terminating the COHO proposal and ensuring that no new Dutch entity or person(s) assumes similar powers, (iv) ensuring that the powers proposed in the COHO legislation and other executive and legislative authority remains exclusively with the elected island governments; and (v) permitting the islands to access international capital markets without interference or any actual or threat of reprisal; support a process by which Sint Maarten and the other islands of the former Netherlands Antilles may finalize decolonization; and adopt such other measures as the Special Rapporteur and OHCHR deem necessary and appropriate.

Respectfully submitted,

/s

Peter C. Choharis

Counsel for Petitioners The Choharis Law Group, PLLC

1300 19th Street, N.W. Suite 620

Washington, D.C. 20036 www.choharislaw.com

Exhibit 1

Knops October Letter

(Original with English Translation)

Dear Mr. Irion,

As you know, a bullet loan of ANG 50 million from the Netherlands to Sint Maarten will expire on 21 October 2020. For ten years it has been known to Sint Maarten that this loan has to be repaid. Although I of course have understanding for the fact that the effects of Hurricane Irma have required a great deal of your attention and energy in recent years, this does not diminish this payment commitment, to which the Cft has also repeatedly drawn your attention. On September 17th, last, you submitted a loan request to the Cft for refinancing of this loan. The Cft was not in agreement with this proposed loan request and has indicated that decision-making on this request should take place in the Kingdom Council of Ministers (Cft 202000132). You have therefore requested that this point be referred to the next Kingdom Council of Ministers.

Since the Kingdom Council of Ministers on October 16th, upcoming will not go ahead, and your loan expires on October 21st, upcoming, I am letting you know by this means of this letter that I am prepared to grant you a four-week extension for the repayment of the ANG 50 million loan, in order to prevent a technical default on the part of Sint Maarten, with all its consequences. These four weeks will give you the opportunity to meet the conditions attached to the second tranche of liquidity support. If you comply, our countries can discuss the third tranche of liquidity support with each other, while we can also discuss a longer-term solution to the expiring loan. However, this goodwill on my part will expire if you continue to seek a domestic loan for which no approval has been obtained from the Cft.

I am referring, of course, to the prospectus that the CBCS published on

October 14th last for a domestic bond of ANG 75 million for the country Sint Maarten. The Cft informed you on October 12th last, that by floating this bond, you are acting in violation of Article 16 of the Rft (Cft

202000143).

I therefore call on you to, in accordance with the letter from the Cft, cease the procedure which you started, and to place a loan request with the accompanying documentation on the agenda of the next

Kingdom Council of Ministers for correct and lawful decision-making.

A copy of this letter will be shared with the Cft.

Yours sincerely,

The Secretary of State for Home Affairs and Kingdom Relations,

R.W. Knops, Msc.

Exhibit 2

Knops December Letter

(Original with English Translation)

The Prime Minister of Sint Maarten

As for Ms. Silveria Jacobs

Government Administration Building Soualiga Road 1 Philipsburg Sint Maarten

Also by email: silveria.jacobs©sintmaartenciov.org Cc: CVoges@kgmsxm.nl

Dear Mrs. Jacobs,

On November 13 last, technical discussions have started on the Netherlands’ offer to Sint Maarten for a third tranche of liquidity support including the conditions attached to it. The aim is to reach a political agreement at the National Council of Ministers (RMR) on 18 December. Yesterday, I learned that Sint Maarten has decided to abandon the Development Policy Operation (DPO), which has now been agreed on all points at official level and the technical discussions have been completed. That’s a meaningful step. However, it does not mean that everything is now ready for a political agreement next week. As you know, it is necessary to take two more important steps. You need to organize political support in your cabinet and parliament, and you must meet the conditions of the second tranche of liquidity support.

Conditions second tranche of liquidity support

On December 8, I have received an opinion from the Financial Supervision Board Curaçao and Sint Maarten (Cft), which shows that Sint Maarten has not yet fully complied with the conditions of the second tranche. The CFT concludes that although you have made progress on legislative trajectories in recent weeks, it is uncertain whether any decision-making will take place by parliament this year. In addition, not all measures have been implemented by Sint Maarten at present. This means that these measures must still be implemented retroactively in the shortest possible time.

In the technical discussions, the question has already been asked what Sint Maarten will do in order to give the Netherlands sufficient confidence in good time that it will actually come to the adoption of the legislation and its implementation in the short term. We have not yet received a reply. However, the Dutch cabinet needs this confidence in order to be informed on 18 December to be able to sign an agreement. I therefore ask you once again to let me know how Sint Maarten intends to implement the measures that will be implemented in the near future to 1) the retroactive reduction of 25% of the total package of working conditions for State members and ministers, 2) the retroactive reduction of 12.5% of the total package of working conditions for (semi)public sector workers and 3) the standard of top incomes. I would ask you to pay attention to the way in which Sint Maarten can guarantee to the Dutch Cabinet that this will actually happen in the shortest possible time, even after an agreement has already been signed. I would like to receive this explanation tomorrow, Friday 11 December 2020.

Political support

In our conversation on 11 November I have already indicated that an agreement is only possible if there is sufficient political support for Sint Maarten. Not only in the cabinet, but also in the States. I ask you to clarify this in the form of a statement or motion by Monday 14 December at the latest, so that sufficient time remains to offer the RMR, if all the conditions are met, the documents for an

agreement. This declaration or motion should show that there are no more incongruousness with the motionnof the United People’s Party and the National Alliance on(completion of complete) decolonization, which was adopted in the States of 5 November last. I stress once again that a motion or other kind of declaration of support by the States is a firm demand for me to reach an agreement.

Finally

I don’t need to remind you that on December 18th, the extended deadline for repayment of the last bullet loan will also expire again. As has already been indicated, I do not see any scope for further extension without an agreement. The potential consequences of a technical default for Sint Maarten are obviously known to you. I therefore sincerely hope that your cabinet will be prepared to take the necessary steps and that we can continue to do the right things for the people of Sint Maarten.